Self-replicating programs

Let’s talk about self-replicating programs:

A self-printing program - or quine - is a program that, when executed, prints it’s own source code.

Why is this even relevant? Well, think about DNA, biological reproduction or even the RepRap 3D printer movement.

There are many quines that you can see just with a quick Google. However, seeing them will give you no insight into self-replicating programs. Most are quite obfuscated and resemble esoteric code that appears to be the product of a convoluted form of prestidigitation. While they function, they often seem more like a way for the author to showcase their skills rather than a genuine exploration of the concept.

In this post, I’ll motivate and build step-by-step a simple Python quine.

Let’s go.

Spoiler alert: My Python quine

It’s rather short:

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))' % (a, a))

This is what comes to the terminal when I run that code:

>> python quine.py

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))' % (a, a))

I can run it forever and it will always print itself, in an endless loop of execution.

Exploiting the syntax

There are many techniques to build quines but here I’ll use the following: exploiting a certain syntactic feature of a programming language.

In my case, the Python feature that I’ll use is string formatting:

a = 'hola'

print('%r' % a)

which prints:

>> python quine.py

'hola'

The thing to note is that the printed result, 'hola', includes the quotes. That is the feature I’ll exploit later. You’ll soon see why this is important.

Printing the print

Now that we have a way to print with quotes ('_'), we can start building the actual quine. The first thing that I did was to print the first line of the program using string formatting again:

a = 'hola'

print('a = %r' % a)

>> python quine.py

a = 'hola'

That’s progress.

Now, I’ll try to also print the second line. If successfull, the quine is done.

First, I’ll print the print():

a = 'hola'

print('a = %r\nprint()' % a)

>> python quine.py

a = 'hola'

print()

Last, I’ll print the contents inside the print(). How? Easy: I can use a to hold the string inside the print().

The following snippet is a bit mind-bending. But it’s not too difficult to understand if you stare at it for a little while:

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r)' % (a, a))

>> python quine.py

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r)')

Ok, I made it quite far. But see the isue? The last part of the original program, % (a, a), is still missing

How to achieve it?

Breaking cycles

My first instinct to print the % (a, a) would be to just add it to the contents of a.

However, that doesn’t work:

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r) % (a, a)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r)' % (a, a))

>> python quine.py

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r) % (a, a)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r) % (a, a)')

# ^ misplaced quote

We’re facing a common challenge when building quines: how do we print the quotes (')?. If I was to include them in the print() statement, like print(" 'hola' "), then how would I print the " quotes now?

Building quines is all about breaking recursion cycles:

print('hola') -> print("print('hola')") -> print('''print("print('hola')")''') -> ?

After all, if a program were to print itself, it would mean -naively- that it should contain it’s own source code plus the code that prints the source code. But then, it’s source code should also contain the code to print itself. That’s a recursion cycle and it’s problematic. The goal is to break it somehow.

Some people address this challenge with a nifty trick: they print the quotes using their ASCII characters:

print(chr(39) + chr(104) + chr(111) + chr(108) + chr(97) + chr(39))

'hola'

That’s, in theory, just exploiting yet another syntactic feature of the language. However, I don’t like to depend on ASCII for my quine to work. It feels rather like a dirty trick.

Instead, I’ll use a different technique. Actually, I’ve been using it since the beginning of this post: remember when I said I would use string formatting as my core syntactic trick? Well, this is why: it allows me to print quotes without having to write the quotes explicitly in the print.

How can we print the following string?

print('hola')

I can use the following source code

a = 'hola'

print('print(%r)' % (a))

>> python quine.py

print('hola')

See where this is going? Using string formatting allows to print quotes without actually having to include the quotes to be printed in the print statement. That breaks the recursion cycle!

Last details

Now, back to the quine. Before we had:

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r) % (a, a)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r)' % (a, a))

Which printed, erroneously:

>> python quine.py

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r) % (a, a)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r) % (a, a)')

# ^ misplaced quote

What if we include the % (a, a) in the print()? We must escape the % with %%:

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))' % (a, a))

>> python quine.py

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r)' % (a, a))

# ^ I must place %% (a, a) after here

Almost there. One last fix…

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r) %% (a, a)'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))' % (a, a))

And there it is. The final quine:

>> python quine.py

a = 'a = %r\nprint(%r %% (a, a))'

print('a = %r\nprint(%r) %% (a, a)' % (a, a))

Quines and DNA

Let’s consider DNA from an information processing perspective: DNA can be viewed as a program that, when executed, carries out specific actions and replicates itself. The mechanics of how a program achieves this are complex, and naively one might think that that capability might not even be feasible.

However, I hope that by this point in the blog post it feels somewhat possible that such a program might exist.

In fact, with a slight modification to the Python quine that I found before, I can enable the program to perform actions beyond mere self-replication. Just as DNA.

The following Python quine can be thought as a model of what DNA does:

a = 'a = %r\ndo_other_stuff()\nprint(%r %% (a, a))'

do_other_stuff()

print('a = %r\ndo_other_stuff()\nprint(%r %% (a, a))' % (a, a))

Upon being run, the code executes do_other_stuff() which may have side-effects (e.g. create proteins), and finally it prints itself (or copies itself to a new cell).

(Sorry for my loose precision when writing about biology concepts 😅)

Wrapping up

I know, it takes a while to wrap one’s head around the syntax acrobatics in quines.

One methapore I read somewhere which helped me build intuition around how quines work is the following:

Imagine you’re playin a game -one very boring game- called

SIMON REPEATS. It’s like Simon says but instead of saying, you repeat what you’ve been told. For example:SIMON REPEATS HOLA --execute--> HOLA HOLAIt gets interesting if the argument is the same as the instruction.

What happens if we pass

SIMON REPEATSas an argument?SIMON REPEATS SIMON REPEATS --execute--> SIMON REPEATS SIMON REPEATS --execute--> ...You get the point: it goes on forever.

See? We have a loop. Or a cycle. Or a fixed point of the instruction.

In a way, quines are a fixed point of the underlying execution model (call it programming language or DNA operation): upon being executed, they produce a result that is ready to be executed again which, in turn, produces the same result.

Self-replicating stuff is great!

If you want to continue exploring this fascinating subject (that of entities that contain themselves), I recommend:

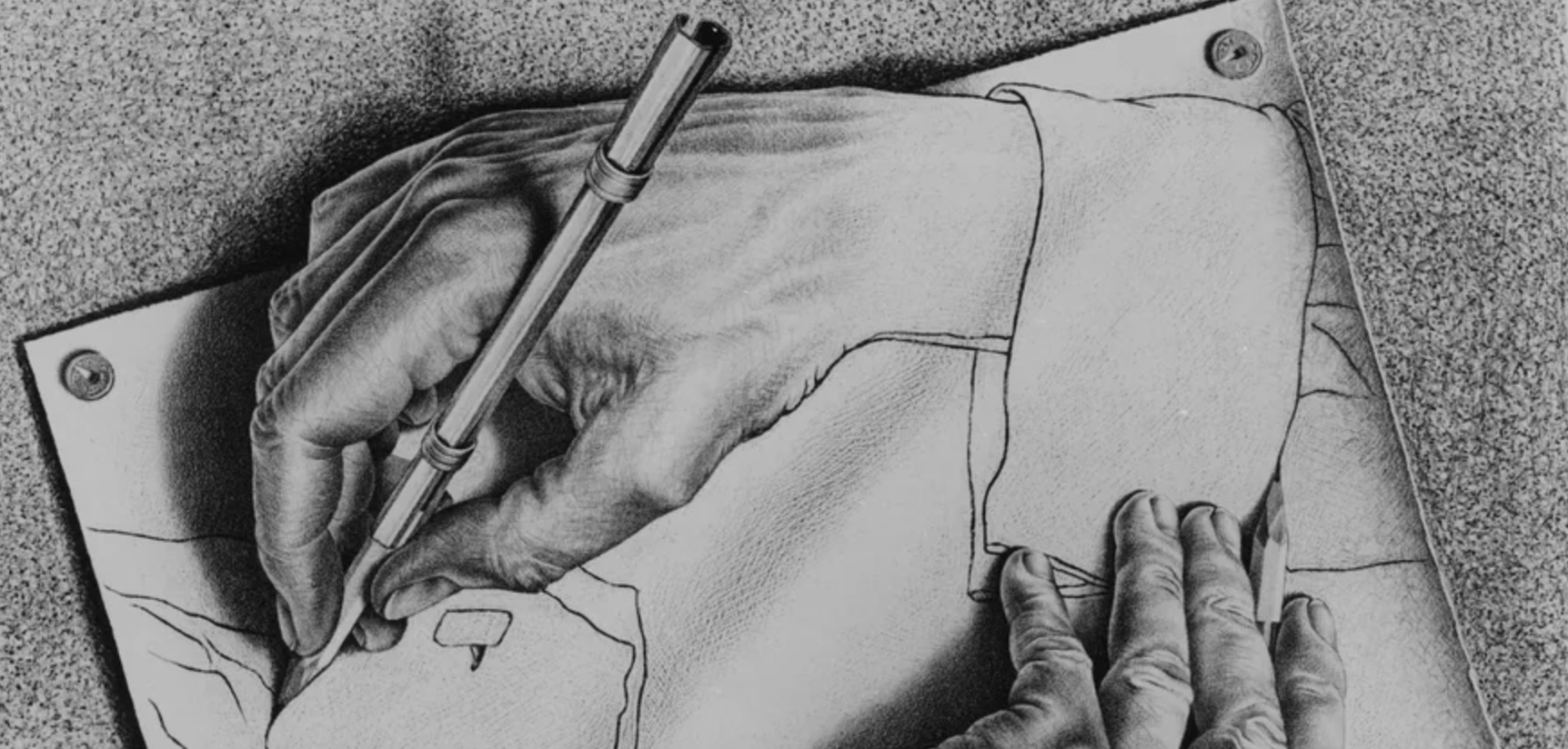

- Godel, Escher, Bach - D. Hofstader

- El Aleph - J. L. Borges